Evangelization and the Catholic University

In a recent conversation with a friend about our university’s mission, I found myself feeling a bit like Ulysses, facing the twin dangers of Scylla on my right and Charybdis on my left (but thankfully, with no Wandering Rocks in sight).

The question was twofold.

Scylla

On the one hand, how is our university different from other liberal arts universities that emphasize classic books and cultivate a robust and traditional approach to liberal learning through our core? In short, what makes us different from St. John’s College, an exemplary institution for engagement with classic books but an institution that lacks any transcendent purpose.

Let’s call this the Scylla question: How does our commitment to liberal learning support our larger mission of proposing the claims of Christianity and then—Deo volente—guiding our students and our community into deeper communion with God?

Charybdis

On the other hand, how is our university different from other Catholic institutions such as the local parish, Catholic Charities, a Catholic hospital, or a Catholic soup kitchen? Isn’t evangelization the goal of all these institutions? Let’s call this the Charybdis question: What distinguishes a Catholic university—in the fullest sense—from these other worthy organizations, or do they all have exactly the same purpose in every way? And if we don’t make evangelization our immediate purpose, aren’t we betraying our calling and becoming just like St. John’s?

By clarifying our identity and mission in relation to these two questions, we may—like Ulysses—wend our way home.

A Solution

Perhaps a key insight comes from this Dominical saying: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’”

Notice how each of the dimensions of the human person, though distinct, is ordered to a single higher purpose, that of love. Each of these dimensions is given to every one of us by God through creation, and we are called to love through these natural means.

And note that these dimensions, or capacities, though good in themselves as natural gifts, are re-ordered by Christ to the highest activity for which we are created. Thus, to study the classic books at St. John’s or any other secular liberal arts institution is to engage with an essential and good part of one’s created nature. The intellect is created to know—even Aristotle recognized that “all men, by nature, desire to know”—and when we seek knowledge, we are fulfilling our nature to a degree.

But we are also called to the supernatural. A Christian studying at St. John’s should—in the wider ordering of activities and loves—seek to structure the study of the classic books in relation to his or her supernatural calling to communion with God. This does not diminish the intensity with which these studies would be undertaken but instead places that study against a transcendent horizon and orders it toward the Beatific Vision. But such a person would not find institutional support from secular liberal arts college and would risk becoming lost in Dante’s “dark wood.”

Thus, to avoid Scylla, our university calls its students to engage with the substantial wisdom to be found within the disciplines of our core but always in a way that is informed, illuminated, and constantly drawing them toward an ever deeper communion with the Trinity.

This is not a demotion of liberal learning but rather its transfiguration.

But what of Charybdis?

How do we distinguish the work of the Catholic university from that of the Catholic hospital, Catholic soup kitchen, and Catholic charities?

While keeping our ultimate purpose clearly in mind—drawing the members of our community into ever-deeper communion with God—we, as a university, have more immediate or proximate ends. Yes, the Catholic hospital ultimately calls all of those whom it serves into a spiritual communion, but its immediate purpose is to heal the body, bringing its patients into a state of health. If I am having a heart attack, now might not be the best time for an extended sermon. If I have not eaten in two days, feed me first and then introduce the good news of the Incarnation and the mysteries of the Trinity. And if I think that I am merely a material being with no higher purpose or destiny, then lead me to the truth of my created nature, a truth that will set me free.

This distinction is crucial: our Catholic university has a dual purpose. Its proximate purpose as a university is to bring our students from a state of not knowing to the possession of wisdom, a truth that will set them free and set them on the road to flourishing in this life and the next. Its proximate purpose is deeply philosophical but also practical. But we do all of this within the larger context of evangelization—understood as proposing the source of Truth and leading others toward Christ—as our ultimate purpose.

A Final Qualification

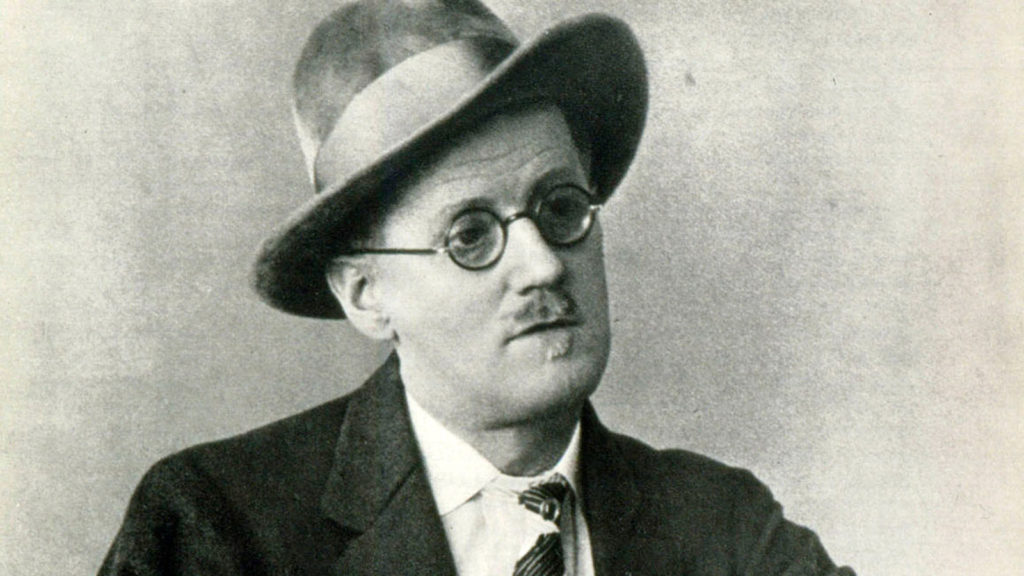

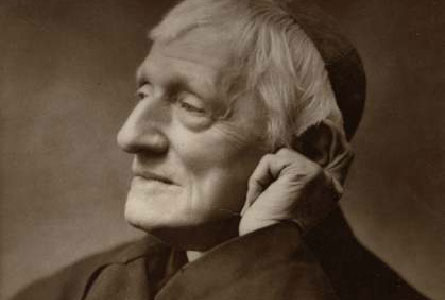

One other qualification should be kept in mind. If our students took their meals off campus, received health care and counseling off campus, and lived off campus, and we were across the street from a vibrant parish that offered a liturgical and sacramental life with outstanding ministries to students, the university could focus exclusively on its essential mission: loving God with our mind, bringing students from Plato’s Cave into the Light. This is what Newman meant by the “Idea” of a university, essentially the life of the classroom and the relation between teacher and student.

But these conditions do not obtain. We do provide housing, counseling, dining, sports, the sacraments, campus ministry, and more. This is the reality of the modern American university. And for this reason, in light of this historical situation, we must seek to provide all of these other services in a way that is consistent with our Catholic identity and the truth of the human person, something that is not always easy.

Thus, the last temptation is to conflate these important but non-essential services with our essential mission: “Catholic Intellectual Search and Rescue” (i.e., the Catholic university) brings students to the Truth that sets us free. And bringing our students to the Truth—in the comprehensive sense of “Wisdom”—is just as important as feeding, providing shelter, and emergency surgery. It may not be as urgent at a given moment of crisis or severe deprivation, but it is at least as important and arguably more important (once the crisis is resolved).

In conclusion, may we, as a university, grow ever more faithful in carrying out both our proximate and ultimate purposes while learning to distinguish between them. Let us spur one another to love God with all our heart, and with all our soul, and with all our mind, and with all our strength, recognizing that it is at a university where students best learn to love God with their minds. We have a unique mission.