Four Fathers of the Core Renewal

If Dante may be permitted to place the Trojan Ripheus in Paradiso—Ripheus having been baptized more than a thousand years before Christ and sponsored by the theological virtues Faith, Hope, and Charity—perhaps we might be allowed the license to imagine the baptism of the renewed Core at the University of St. Thomas. If so, who might the Core’s sponsors be?

Among the possible sponsors, many of them ancient and medieval, there are four recent figures that could claim that title. Inspired by their teaching, example, and the ethos with which they joyfully cultivated the life of learning, members of the University’s faculty have prepared a renewed core curriculum that will form our students for flourishing in this life and in light of eternity.

Pope Saint John Paul II

John Paul II, in his encyclical Fides et Ratio (1998), not only treated the relation between Faith and Reason, but also proposed that the search for wisdom is a universal quest that belongs to every person and every culture. This quest, which he calls “Philosophy,” is animated by wonder and fundamental questions that are innate to the human person and that compel us to seek answers.

Though we may defer addressing these questions or attempt to distract ourselves from them, these questions never fully fall silent. In the context of a Catholic university, these questions can find their full voices again and become ordered to their proper purpose, the search for truth and communion with the author of all Truth. Through their teaching, our faculty reawaken this natural desire for wisdom that is latent within us all and that enables us to ascend toward a vision of the Good. Thus, within the core of the University of St. Thomas, we not only clarify the complementary nature of Faith and Reason but cultivate and illuminate these fundamental questions. In doing so, we seek to enkindle wonder within our students and in one another, finding again the “desire to know” that stands as an ineradicable feature of what it means to be human. Having been recovered, these questions then become the motive force of the core, animating students to seek answers that will shape them for the rest of their lives and be handed on to their own children.

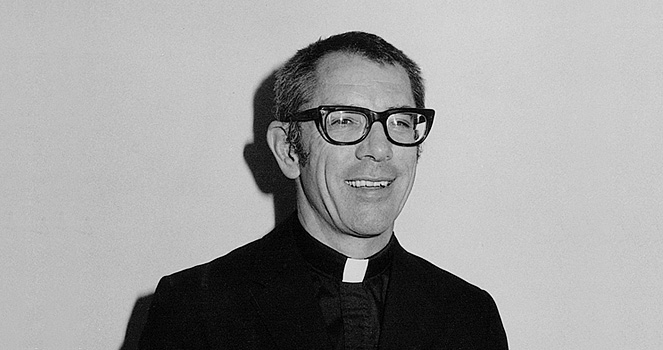

Fr. James Schall, S.J.

Among his contemporaries, Fr. Schall stands as one of the great teachers and writers who—with good humor, grace, and gentle encouragement—tirelessly led his students back to the classic books that must nurture any education that is truly liberating. And if the perennial questions suggested by Fides et ratio constitute the animating “soul” of liberal learning, then these classic books and authors to which Fr. Schall tirelessly directed us are the “flesh” in which liberal learning is embodied. In bringing our wonder-inspired questions into dialogue with the books and their authors, our faculty seek to discover both the universal wisdom the books contain as well as the insights to be gained through a more focused disciplinary perspective.

Indeed, we can say that Fr. Schall teaches us to approach each discipline and each classic book with a philosophical spirit, sharpening a vision born of wonder. Inspired by his example, our teachers cultivate within the almost-sacred space of the classroom the dynamic, life-giving relation between student and teacher. Neither ponderous nor pedantic, always delighting in the joy of learning, and indefatigably inviting those who might be lingering at the back of the classroom, Fr. Schall offers an example of the teachers our students most need today.

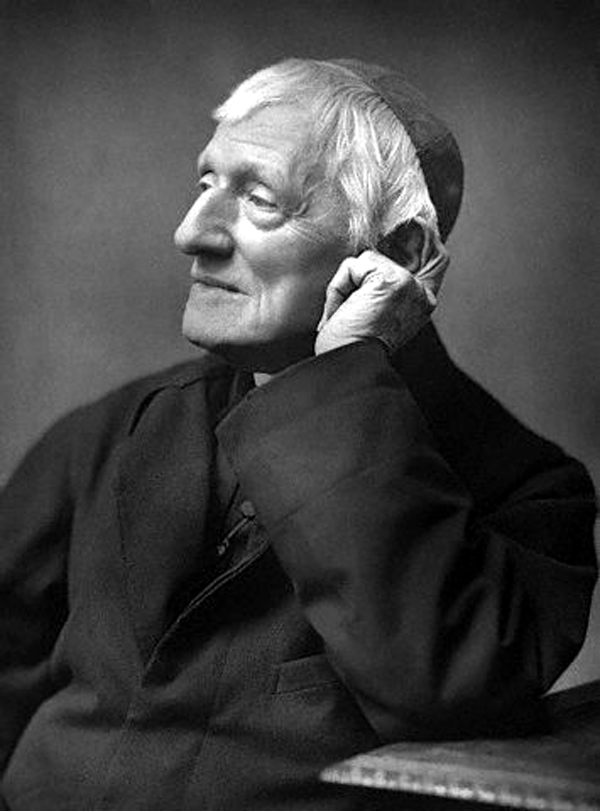

Saint Cardinal John Henry Newman

Cardinal Newman, through his many writings—including the Idea of a University, The Rise and Progress of Universities, and his essays on St. Benedict—reminds us that liberal education is not the same thing as holiness and that the university should be universal in scope, integrating all disciplines of knowledge within an ordered “circle of the sciences.” But he teaches us much more.

In Newman’s vision, theology, as the queen of the disciplines, holds an honored place and fulfills an ordering role, ensuring that a full integration is maintained among our disciplines and enquiries. (For the good of the whole and for the good of the disciplines themselves.) By considering Newman’s writings cited above in conjunction with one another, Cardinal Newman also gives us a vision of the university life conceived in its entirety, one that integrates the teaching of the classroom—which he called the activity of the University”—the tutoring, residential, co-curricular, and spiritual dimensions of the university—which he designated as the activities of the “colleges”—and the role of the Church in ensuring the integrity of the institution.

And to complement his more theoretical and historical writings, he also offers his example of founding and leading a university. This included writing a “student-life handbook,” conferences with anxious parents, and dealing with loud and drunken undergraduates who misbehaved in public, among other typical tasks of running a university.

Finally, he confirms for us that our students will be formed in two primary ways and that if we ignore one or the other of these, we will risk institutional shipwreck. The first is through teaching in the classroom, i.e., the essential activity treated in the Idea of a University. (Many readers assume that Newman’s Idea is a comprehensive account of his vision of university life. It is not.) The second is through the personal influence of faculty (as well as staff, and administrators) outside the lecture hall, a vision he articulated most clearly in his Rise and Progress of Universities.

In light of this last truth, we will remember that those whom we hire to teach must be capable and trustworthy in both domains. Our faculty must not only attend to what they convey in the classroom but also their influence beyond it, in those conversations before and after class, over coffee, or before Mass. Like Newman, we must keep both the parts and the whole of the university in a coordinated and integrated vision.

Josef Pieper

But whence does our liberal learning arise and at what does it all aim? Josef Pieper clarifies for us both the origins and telos of our pilgrimage of liberal education. These he finds within the teachings and example of the pre-Christian ancients and his great teacher, Thomas Aquinas. The origin of our journey is born in Plato’s Academy and our aim is nothing short of a never-satisfied, open receptivity to all of reality expressed primarily through a contemplative and joyful affirmation of the goodness of God’s creation and Being itself.

Under Pieper’s direction, we cultivate the wonder and leisure that is born from worship and true festivity, so that we and our students can come to know ourselves in the light of Truth, develop the capacities of the mind and heart that make us fully human, and attain to a deposit of wisdom that can be developed over the course of a lifetime. Through this process—when carried out with humility and blessed with grace—our students can come to flourish in this life as they prepare to flourish in the next. Indeed, with this preparation, they can live lives of self-giving, as they renew the original calling that we all share, to be good stewards of the garden of the world. And not paradoxically, students and teachers alike will come to recognize that human flourishing may, just may, include martyrdom.

These four figures, our “sponsors” as it were at the baptism, represent the dynamic structure and sources of our renewed core, a core unparalleled among others in the nation. Animated by the rediscovery of wonder and recovery of universal questions, we introduce our students to the great dialogue across time that is embodied in the classic books and disciplines, all ordered within a symphony of knowledge, remaining tireless in our search for Wisdom.

Of what we have received from our Basilian founders and our patron St. Thomas Aquinas, let us be good stewards, so that we may pass on our inheritance to future generations and hear the words, “well done, good and faithful servant.”