Solidarity as the Basis of Community in University Life

It is common to speak of “community” when discussing our academic institutions. As Christians, we often hear the resonances between “community” and “communion” and allow these resonances to summon the suggestion of a sacramental vision of the classroom and the activities we undertake therein (as well as in other places on campus). But another angle of vision that may illuminate the term “community” in an academic context derives from the virtue of solidarity. How might seeking to understand, acquire, and enact solidarity in the context of academic life help us to realize community and rescue it from being simply another banal slogan?

For many of us, the word “Solidarity” conjures memories of the heroic Lech Wałęsa and Pope John Paul II overcoming tyranny in communist Poland. Or it may summon the full complement of principles that constitute Catholic social teaching, teaching that seems increasingly difficult to apply to the contemporary social challenges that roil our nation.

Yet this principle, cannot be dismissed as merely aspirational. Rather, fully understood and prudently applied it provides the vision and resources that we need at this moment both in our national life but also within our universities in order to repair our fraying social fabric.

But what is solidarity? Though often difficult to define and describe, there is—across classical and contemporary authors—a remarkable consensus.

First, it can be understood not as a mere passing sentiment but as a virtue that is built up over time in an individual’s soul. Through intentional practice this building up will, when the virtue is formed, enable a certain type of fluent and more-fully human action. As a moral virtue it remains invisible, unless it is brought to light through action or culture, i.e., the things that our actions produce over time such as laws, customs, and institutions.

Recall how justice or courage are similar. Through intentional activity, we create the stable dispositions of courage and justice in our souls that we can then bring into action, doing courageous and just deeds at the right time and in the right way. We don’t become courageous and just overnight. It takes time, intention, and sometimes a teacher. But the virtue, once established, is there within the soul, relatively stable, and ready to enable us to be more completely human.

Similarly, the justice in our souls can become embodied in just structures such as law, institutions, and practices. And courage can become embodied in groups in which the courage of individuals is compounded and expressed through heroic deeds and traditions marked by heroism.

In the same way, solidarity—understood as a virtue—will be built up over time, remain stable within us, usually remaining hidden until brought into action, and lead to the creation of cultural institutions, traditions, and expressions. Conceived in this way, solidarity becomes much more than a passing sentiment but is something we can consciously cultivate in our souls and in our institutions in the same way we cultivate justice and courage.

Second, we can clarify the object to which it is directed and the sources upon which it draws. Stated simply, it is the virtue ordered to the common good which, in its fullest sense, possesses a kind of “dual citizenship” enabling it to build up and integrate the natural and supernatural dimensions of well-ordered human social life. As a virtue it brings to action through a stable disposition an enduring commitment to just relations between the members of society and their common good while going beyond justice in ways that require sacrifice. Such sacrifice might be a simple sacrifice of material comforts for the sake of others or could be embodied in heroic self-sacrifice.

In this way, even in its natural form, solidarity adds kindness and generosity to justice, cultivating a kind of “charity” born from a sense of our common humanity reflected most directly in our common powers of reason and speech. Here, within natural solidarity, the spheres of the virtue are drawn around us hierarchically in each of the “societies” in which we live—following Cicero—as members of our given nations but also in more limited form by enclosing the smaller societies of which we are a part, such as parents and children, our extended families, and in a particular way in our friendships. In light of the latter, it is of more than historic interest that one of the early terms for what we now call “solidarity” was “social friendship,” the extension of friendship to larger social groups.

At a supernatural level, solidarity extends what nature requires or urges upon us is in two dimensions. First, solidarity may extend itself in the actions we take and the sacrifices we may be called upon to make. Second, solidarity may be extended beyond the natural depths of common fellow-feeling and our common humanity to transcendent hidden sources—transfigured by grace—that give birth to heroic virtue and nourish the actions that spring from it.

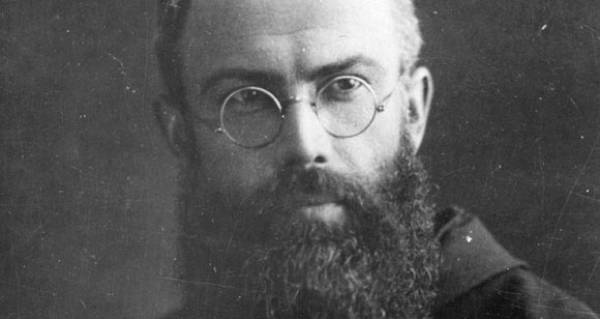

In the first dimension of virtuous action and fulfillment, supernaturally informed solidarity summons us to divine charity and self-sacrifice. Christians seek to stand ready to realize within our common social life—in the right time and the right way—the example of divine self-giving. For Christians the models for this take the form of the Paschal mystery and the sacrifice of martyrs such as Maximilian Kolbe, who volunteered to die in place of a stranger at Auschwitz.

In the second dimension, looking to the sources of supernatural solidarity, one recalls that for Christians, solidarity is ontologically grounded in and animated by the life of the Trinity and the communion of saints. Reality itself, at its deepest level is a self-giving-and-receiving unity of persons in a communion which overflows into creation and most clearly in creatures made in God’s image.

Further, Dostoevsky’s Father Zossima suggests the primary fonts from which supernatural solidarity can spring. In Book VI of Brothers Karamazov, we encounter a series of stories and sermons that reveal both what the highest forms supernatural solidarity might look like as well as the conditions that make such forms possible.

Such supernatural solidarity requires above all a supernatural horizon and orientation. If it is not present initially, it can be achieved through a “breaking in” of the divine that reorders our fundamental vision of reality. This can be induced through almost-sacramental encounters with nature, through violent acts—our own or others—through severe illness or other means. These in turn can lead to repentance and the reordering of our lives in relation to God and others animated by grace. And finally, this reordering takes a more permanent form of practices through which the new vision and grace-filled life unfolds over time.

Only through these means can a natural solidarity of Cicero become the solidarity of Maximilian Kolbe

Finally, following Aristotle, we can better understand a virtue by considering its correlative vices. But what are the vices that oppose solidarity? On the one hand there is the vice that we might call “isolating individualism.” Tocqueville was eloquent about how individualism—particularly in its American form—separates us not only geographically and but also temporally, i.e., those who come before us and those who will follow us. It cuts us off from those to whom we should be naturally linked and for whose common good we should work through both discrete actions but also through the creation and renewal of culture.

The opposite vice that opposes solidarity might be called “false solidarity,” being false because of its disconnection from truth and the proper sources that should animate it.

In this way, solidarity can become false by attempting to establish it on terms that ignore both the sources of natural and supernatural solidarity outlined above. In this case good intentions become utopian visions, often animated by ideology. It was just such an attempt that summoned the Polish solidarity movement in response to the dystopian “solidarity” of the community party.

Similarly, and more commonly today, we see false solidarity established on resentment or feelings of victimization not based on class but on other categories of identity. Here the victims are joined together against a common oppressor. This solidarity can also be ordered hierarchically but along the lines of intersectionality, enabling one to have a greater claim to solidarity—and supposed remedial justice—depending on the cumulative types of oppression that one can claim to suffer.

But a moral virtue cannot be fully itself in its theoretical form. Like the cardinal virtues of courage and justice, solidarity can only be itself when fully realized in action.

So how might we acquire and live out the virtue of solidarity in our own age, within our nation and our universities? For people of faith, we will recognize both the natural sources upon which we can draw but also the need for supernatural aid.

From Cicero and other authors in the classical tradition, we can learn to cultivate the natural virtue ordered to building up the common good in which justice extended by generosity marks our social and civic interactions and the cultural expressions we support. But even with the best of intentions and disciplines, we will no doubt find ourselves sometimes straining not only to fulfill what nature suggests but also seeking to go beyond what nature would require. Here the life and direction of Dostoevsky’s Fr. Zossima can assist, guiding us to the supernatural resources and disciplines required for heroic solidarity. We might take up the spiritual disciplines, deepening the channels of grace in our lives so that we can then strengthen the bonds that already exist naturally with our neighbors while reaching out to strangers who are peripheral to our lives. Perhaps—as one Dostoevsky’s character suggests—we could begin by asking for forgiveness or extending hospitality to those who least expect it.

Each of these themes, questions, and applications are born from texts by Dostoevsky, Cicero, Sacred Scripture, Pope Saint John Paul II, Roger Scruton, and Russell Hittinger, texts that formed the substance of this summer’s First Things “Intellectual Retreat” in New York, a retreat in which I was privileged to particiapte. The retreat—a joyful integration of seminars, lectures, and panels complemented by good food and wine with friends in a beautiful setting—led many of us to both greater clarity about the nature of solidarity and how we might grow in that virtue in our lives.

Though no definition would be fully satisfactory, we did—in one of our final seminars at the retreat—propose a description that draws together much of what is outlined above. We proposed that solidarity is a moral and social virtue ordered to building up the bonds of friendship within a society, drawing upon both justice and kindness. In its natural form, it emerges from an awareness of our common humanity that springs from our common capacity for reason expressed through language and dialogue. Though this natural solidarity might theoretically be extended to all men in attenuated form, practically and typically it is active within hierarchical spheres of social concern that include our nation, our parents, our children, our extended families, and—in a special way—our friendships. But this natural solidarity can be transformed and transfigured by grace, recognizing its roots in a shared imago Dei that is shared even by our enemies and those who cannot engage in rational activity, and extending its reach—in actual practice—to total strangers, something exemplified by St. Maximilian Kolbe and ultimately by Christ himself.

In sum, we concluded that this is a virtue that—in its natural form—makes us more fully human and in its supernatural form, can make us more than human.

Community within a University

This extended meditation on solidarity brings us again to the question of “community in university life.” I hope it is clear by now how this virtue, needed now more than ever, can be an animating principle not only for our nation but also the community formed by our university. As a microcosm of our larger society, our university needs both the natural and supernatural resources to build up and make actual the virtue of solidarity as the basis of community. Though Christians share a bond through faith—and in this context communion becomes our standard—universities such as ours bring together individuals from different religious traditions (or no tradition at all) in a society devoted to the life of the mind. In such a mixed community, the natural virtue of solidarity becomes critical, even as supernatural bonds are nurtured and extended through grace over time.

Thus, when we speak of “community” at our university, let us immediately invoke solidarity, lest the former devolve into mere sentiment or empty slogan. If we want to create a stronger community at our university, let us each build up and practice in concrete ways each day, the virtue of solidarity. It is this virtue—both in its natural and supernatural forms—that will make our academic association a true community and serve as a bulwark against the forces that would seek to divide us.

A version of this post appeared on the First Things website in late August.