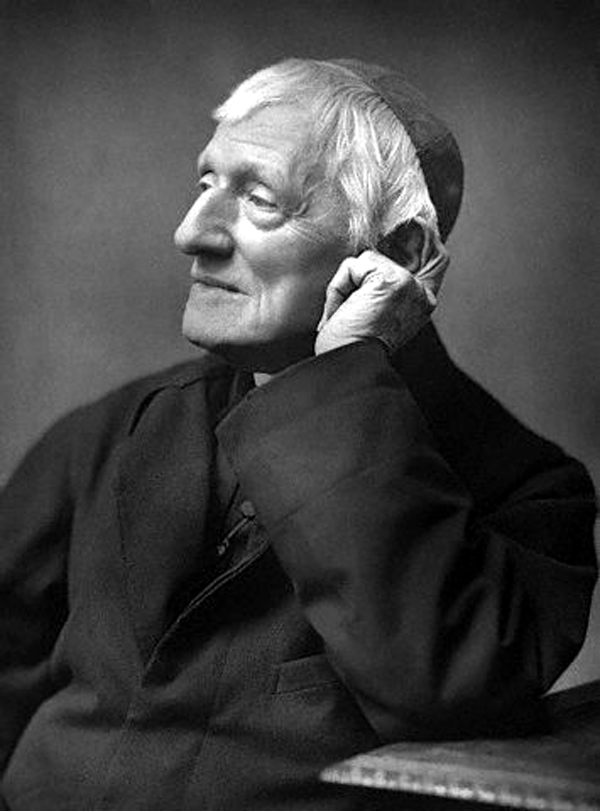

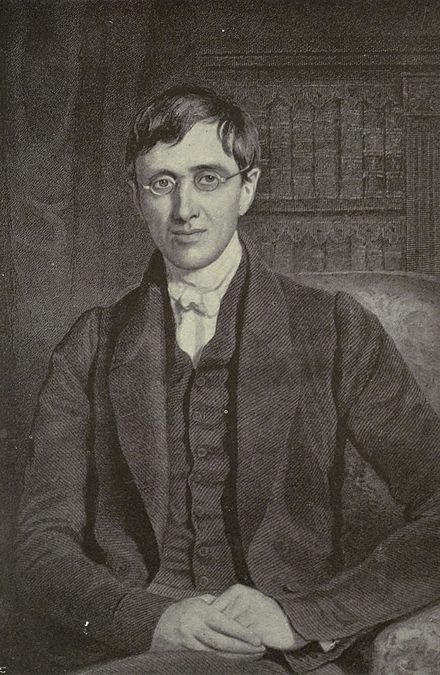

Four Lessons for a Catholic University from Newman on his Feast Day

by George A. Harne

A version of these remarks was offered on the Feast of Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman in the Faculty ‘Newman Room’ at the University of St. Thomas on 9 October 2023.

Welcome to all who have joined us on this feast and welcome to a very special place here on our campus, the Newman Room in Hughes House.

I’ve been asked to offer some brief remarks and so I’ll make four observations about the importance of Newman to our institution, four ways in which Newman animates our renewal of the Catholic identity of this university.

First, there is the importance he places on the communion among persons. This is one of the reasons that the room in which we are standing is an apt way to honor Newman. In this place the play of lively minds unfolds through the art of conversation. Here we engage in the rare arts of intellectual friendship that vivify the intellectual Christian life through which we come to love God with both our minds and our hearts. Here we gather for ‘Coffee with Aquinas’ (sometimes also called ‘Cookies with Pieper’). Here the school deans discuss Ex corde ecclesiae and other documents central to our mission. Here faculty come together to discuss readings from the core, such as Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy. And here we bear witness to Plato’s wisdom that the highest insights emerge as a gift when friends pursue the truth together in dialogue. If and when the history of the renewal of the University of St. Thomas during this decade is written, it will be a story of intellectual friendship, cor ad cor loquitur, and the play of lively minds in communion.

And this is one of the reasons that we have resisted the Borg-like mechanization and industrialization of the education we offer. It may have been necessary to move classes online during 2020, but true liberal learning cannot be mechanized and industrialized. It cannot be digitized and mass produced. It can only exist within the give-and-take of embodied souls in dialogue and in person.

Second, we are inspired by Newman not merely to offer a grab-bag of subjects to our students—whatever happens to be fashionable today or this year—but to integrate both perennial and more contemporary subjects into a larger unity that Newman describes as a circle, in which the disciplines stand in harmony with one another and with the whole of human knowing ordered to the highest wisdom. Newman teaches us that the university, if it is to be true to its name and essence, should include all branches of human knowledge, should be a ‘universe’ of disciplines.

But we also learn from Newman that the circle of disciplines should be complete and coherent, i.e., the disciplines should be ordered properly in a way that is intelligible. Without this completeness and coherence, Newman warns us, then disciplines overrun their boundaries and take on authority that not only distorts other disciplines and the whole of learning but even the usurping discipline itself. Thus, without philosophy and theology in their proper place, other disciplines will rush in and seek to instruct us in the ultimate truths about God and what it means to be human. And here also, theology and philosophy play crucial roles, with philosophy helping disciplines to achieve self-knowledge and integrating them into a whole, while theology serves as the ground for all other knowledge, illuminating the disciplines, and placing them within and against the background of eternity.

Third, though this is often misunderstood by many, we learn from Newman that the University seeks to educate the integrated person. In Newman’s vision, this education unfolded in three dimensions that could be signified by the tutor, the professor, and the bishop.

It was in the residential colleges, that is the residences, living and working with a tutor as mentor and guide that students received not only intellectual formation but also personal, moral, and spiritual formation. And this formation was amplified over food and drink, settings to which Newman attributed his deepest formation as a student at Oxford. Though we cannot replicate this in the exact form that Newman experienced it as a student and established at his own university in Ireland, we can and do strive to approximate this at the University of St. Thomas.

But it was alongside the collegiate or tutorial principle, that Newman posited the ‘professorial system,’ in which students learned from the great lecturers, a dimension signified by the ‘University’ in his Idea of a University. It was through this dimension that magisterial teaching received pride of place for the formation of the intellect animated by liberal learning.

And finally, it was the ecclesial dimension within (and beyond) the university and the colleges–a dimension that Newman assumed would exist and be strong–that nurtured the students and faculty through the sacramental and liturgical life and ordered the Catholic university to eternity and the ultimate flourishing of her students. Through these three dimensions we see Newman’s integrated vision for an integrated Catholic education.

Students and their teachers need all three: the tutorial, the professorial, and the ecclesial. When all of Newman’s writings on the university are read together along with the historical accounts of his work at the Catholic University of Ireland, we see that we cannot merely train students for careers and therapeutically manage their appetites through residential and co-curricular policies and activities. Rather, we must call them to lives of intellectual and moral virtue and invite them to embrace liturgical and sacramental discipleship, all the while guiding them from ‘shadows and images into truth.’ Under Newman’s inspiration and, mutatis mutandis, we can form our students as integrated persons, for flourishing in this life and for eternity. Even here and how in this year of our Lord, 2023.

And for Newman, this wasn’t a detached, speculative matter. He did the hard and messy work himself. He dealt with drunk undergraduates yelling obscenities at noble dignitaries passing by in parade in the streets of Dublin. And he comforted parents while telling hard truths in parent-teacher conferences. He even wrote a ‘student life handbook’ based on real-life experience with undergraduates. If we truly follow Newman’s example, we will give teaching and scholarship our highest attention but also not stand apart from the messy business of leading the university and getting our hands dirty in the service to our institution. All who stand in this room today are following Newman’s example.

And fourth (and finally), Newman teaches that the ‘love of learning and the desire for God’ can manifest itself in three distinct modes, all of which can bear fruit and live in complementary harmony with the others at a Catholic university. Though he describes these modes in his Benedictine essays as approaches to the Christian life generally and periods of Christian history, they are equally applicable to the life of the scholar-teacher in the Catholic university. Let us consider them as three concentric circles: the Benedictine, the Dominican, and the Ignatian.

Arranging his three modes in concentric circles and moving from outside to the center, we can say that first, under the aegis of St. Ignatius, we can prepare students for the active life through the practical, applied, and professional arts. There is a place for the Catholic practitioner who forms Catholic practitioners within the Catholic university. We seek to meet the need for this type of person in our professional schools and in our majors ordered to practice.

But universities, understood properly and from Newman’s perspective, are not primarily professional programs for career preparation. As important as it was for Adam and Eve to til the garden and keep it, their higher activity was walking with God ‘in the cool of the day.’ And though Martha’s toils were necessary, we know from our Lord that ‘Mary chose the better part.’ Thus, Liberal learning should be the heart and animating purpose of every university, it should lead to the philosophic habit of mind in the university’s students, and lead them to the top of the mountain for a view of the whole. Liberal education–learning that is at once the most useless thing in the world while being most useful of all–should hold pride of place. This is that at which the Benedictine and Dominican modes aim.

Through the second mode or second circle, under the aegis of St. Dominic and his student St. Thomas Aquinas, we can become builders of intellectual structures and systems that aspire to be comprehensive while being true to the whole of reality and teach our students to do likewise. Thus, there is a place for the systematic philosopher, the systematic theologian, and the builders of systems in other disciplines. To use Tolkien’s language, we can engage in scholarly ‘subcreation,’ ‘worlding worlds’ within the Catholic university for the Church and the greater world. Our Center for Thomistic Studies and our Department of Theology stand foremost as representatives of this mode of intellectual life within the Catholic University.

And finally, at the very center and heart of the university, under the aegis of St. Benedict, some of us can undertake the more modest work of gradually advancing our disciplines with the scholarship and teaching that God calls us to each day, with the few hours we are given, sometimes rising early and sometimes burning the oil at midnight, seeking to be faithful while leaving the completion of our labors and the fruits of our efforts in God’s hands. In Newman’s view, the Benedictine mode nourished the other two modes, and served as their foundation. And just as there is a time and a place and season for each of these modes within the life of a single scholar so also there is room, within a Catholic university inspired by Newman, for all three in institutional harmony.

So, thank you for joining with us today to celebrate this feast of Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman and know that you are always welcome here in the Newman Room to participate in the play of lively minds. Please keep us and our students in your prayers.

Let us raise a toast to Newman on his Feast Day, “From shadows and images into truth.”