Can There Be Too Much Finance?

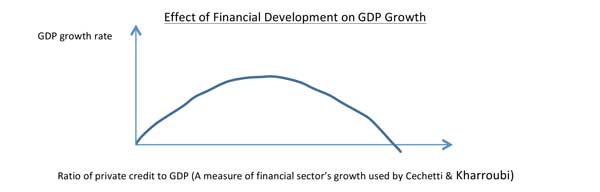

By Dr. Pierre Canac –Finance certainly plays an indispensable and positive role in promoting economic growth and overall employment. However there is some evidence that the relationship between financial development and GDP growth is not linear, but instead has an inverse U-shape. As the size of the financial sector gets larger, at first GDP growth rises, but then the relationship between the two variables turns negative once the financial sector has reached a threshold size (see drawing below).

Correlation versus Causation

A large number of papers have studied this relationship, for example Arcand et al. (IMF, 2012) and Cechetti & Kharroubi (BIS, 2012). However those papers only explain that finance and growth are correlated, but do not prove that it is the size of the financial sector that is affecting economic growth – for example by taking resources away from the real economy. It could be the other way around where economic growth has an impact on the size of the financial sector. For example when the economy is experiencing a low rate of real growth more resources must be shifted to the financial sector in order to locate investment opportunities that are harder to find in a depressed economy.

The Financial Resource Curse

A new paper by Gianluca Benigno, Nathan Converse and Luca Formaro (2015) may have found the mechanism by which the size of the financial sector affects GDP growth, more specifically the negative relationship between the growth of finance and the growth of the real economy (the downward section of the inverse U shape). It requires the intervention of a third factor, the inflow of financial capital from foreign countries. They call this the financial resource curse which is an adaptation of the natural resource curse (also called the Dutch disease[i]). According to this resource curse, countries well-endowed with natural resources export them and in the process experience an appreciation of their currency, which causes exports of manufactured goods to suffer thereby reducing economic growth. Benigno et al. argue that something similar occurs when financial resources flow into a country from abroad. Capital inflows cause the currency of the receiving country to appreciate prompting the country to lose competitiveness. Thus the manufacturing sector that produces tradable goods is negatively affected while other sectors such as finance and construction benefit from the capital inflows. They take the example of Spain, which experienced large capital inflows following the creation and its adoption of the euro in 1999. Its financial sector grew and financed a construction boom as the strong euro hurt the Spanish manufacturing sector. Following the housing and construction crash in 2008, Spain’s banking sector had to be bailed out and its economy collapsed. A similar chain of event also occurred in Ireland. Benigno et al. show that this pattern is not limited to Spain and Ireland, as their statistical evidence is based on 155 episodes of large capital inflows in 70 countries over a period of 35 years following the Bretton Woods era.

Emerging markets also experience volatile capital flows exposing them to this financial resource curse. Thus when the U.S. central bank implemented its quantitative easing program between 2008 and 2014 resulting in low U.S. interest rates, the result was a capital flight into emerging markets (for example Brazil) whose currency appreciated and exports declined reducing GDP growth.

Could the U.S. itself be touched by the financial resource curse? Prior to the Great Financial Crisis the U.S. was experiencing large capital inflows associated with increasing current account deficits; its financial sector grew very large and complex, possibly financing the housing boom instead of Research and Development and investment in productive industries and thus potentially taking resources away from the manufacturing and tradable goods sector. Additional research is needed before reaching a definitive answer as other factors have also affected the U.S. housing boom.

Policy Implications

Developed and emerging countries should adopt different measures to reduce the negative impact of too large a financial sector. It might be sufficient for developed countries to reduce the size of banks which are too big to fail by adopting appropriate regulations, including adjusting their capital and leverage ratios in function of the riskiness of their assets. Developing countries might have to intervene in foreign exchange markets and adopt measures designed to limit capital inflows, especially the short-term and more speculative inflows that are more prone to cause their currencies to appreciate before crashing when the flows are reversed.

Conclusion

Although a case can be made that Finance has grown too big, my intention was obviously not to sway students to major in other fields of business such as Accounting or Marketing. I am sure that a similar argument could be made that our complex accounting laws are not optimal and require too many accountants and that many marketers are involved in dubious strategies designed to create unnecessary needs. However, I believe that it is important for students to be well-informed before selecting a career so that they contribute to improving how businesses serve people and not the other way around.

Pierre Canac, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Economics

References:

Arcand, Jean-Louis, Enrico Berkes and Ugo Panizza, Too Much Finance, IMF Working Paper No. 12/161, June 2012

Benigno, Gianlucca, Nathan Converse and Luca Fornaro, International Capital Flows, Sectoral Resource Allocation, and the Financial Resource Curse, https://voxeu.org/article/financial-resource-curse, 11 October 2015

Cechetti, Stephen G. and Enisse Kharroubi, Reassessing the impact of Finance on Growth, Bank for International Settlements Working Paper No. 381, July 2012

[i] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_disease