Win-win scenarios are generally not the ideal for either party in war or sports.

Sporting events, such as the Olympics, have often superseded the political landscape, offering national pride to the winner, along with boasting rights that may not be possible on the battlefield. With much literature aimed at integrative negotiations, we step back to examine negotiations in sports. In particular, we evaluate negotiations and conflict management styles in a sport more akin to war than most – professional boxing. Through case studies and vignettes, we get an often behind-the-scenes look at the complex world of boxing decision-making. While professional boxers enter the ring with the intent to dominate their opponent by inflicting pain, they do so under contractual obligation to abide by a set of rules. Most rules in boxing are centered around the avoidance of unfair advantage. Thus, for example, we have weight ranges and prohibitions against illegal blows. We have preset time lengths and subdivision into rounds. Combatants agree to be assessed on a point system by predetermined judges, provided fighters are able to successfully complete the appointed maximum duration. The successful referee enforces the rules of engagement without drawing undue attention to himself. In some of the most successful bouts, the referee is the “invisible third man” in the ring.

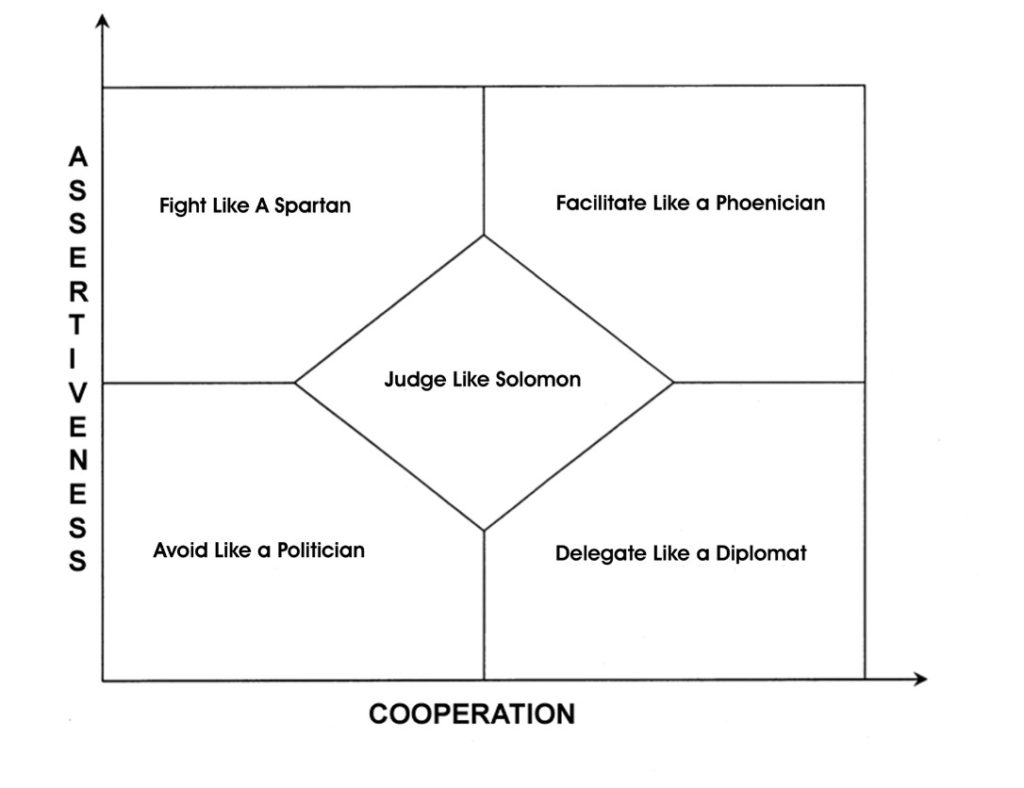

You may be wondering what about in business situations, will there also be a combative type of situation? In cross-cultural business often you got into a conflictive situation without understanding other cultural symbols or context, heritage or traditions. Also, you could be stepping into a conflictive combative situation due to differences in generational management between millennials and gen X or Baby Boomers. This is why the authors have studied professional boxing and negotiations. This modified Thomas Kilmann model proposed by Chamoun et al. could be more suitable to analyze the conflict managing styles in a business combative situation.

Adapting the Classification of Conflict Management

Styles for the Boxing Context

In sports, and professional boxing in particular, it is not readily apparent that parties cooperate with one another to any recognizable degree. Many would rather see only two of the traditional style designations as appropriate: competing and avoiding. As fighters are both dying for a win and working to incapacitate their opponent or his ability, nearly everyone in boxing would categorize a fight as maximum assertiveness without cooperation. Fighters, however, do cooperate to a significant degree to ensure a fair outcome, with significant value for themselves, their business partners, and the fans that ultimately finance the sport. In addition, they cooperate by agreeing to abide by the rules of boxing. They cooperate by agreeing to abide by the instructions of the referee, who serves as both observer and judge.

The referee is present for close-hand inspection of tactics, exercise of penalties, protection of participants, and adjudication. The skilled referee is constantly moving to get the best point of observation, and is ready to intervene in an instant, while avoiding interference. The referee is working with both participants, allowing them to spar with- in the agreed set of rules, but quick to act on either’s behalf should there be a violation or safety concern. The referee must command the respect of fighters often double his size and thrust into situations where emotion often overrides intellect as participants move in and out of positions of dominance. We focus on conflict management styles from the perspective of the professional boxing referee. But first, we adapt the traditional terminology of Thomas and Kilmann, to make it more recognizable within the context of a combative adjudicated sport (see Figure 1).

Competing – Fight Like a Spartan

The Spartans were ancient Greece’s most formidable warriors, with a “win at any cost” attitude, solidified with viable, time-proven battle strategies and an unswerving sense of honor. Boxers will rapidly associate with this style and exhibit it most often in pre-fight rhetoric and assertion of fight control in the ring. It will be most often conferred on the aggressor and is most visible between boxers content to go “toe-to-toe.” The referee also must use this style, however, to command the respect of the fighters in order to maintain control of a bout. Overuse of this style by a referee, however, is not appreciated by fans, who want the fighters to control the outcome. The best referees will judiciously exercise their competitive style, choosing to exhibit enough authority to ensure safety and fairness without being the center of attention.

Collaborating – Facilitate Like a Phoenician

The style high in cooperation and assertiveness we re-labeled as Facilitate Like a Phoenician. The Phoenicians were an ancient Mediterranean people known for their negotiation skills (Chamoun and Hazlett 2008). In a prolonged period of regional conquest, the Phoenicians made themselves more valuable as business partners to the political and military powers in play than as a subjugated people. Thus, we associate conflict management styles that involve a high degree of cooperation and concern for effectiveness with these highly skilled negotiators of the past.

Boxers will not see themselves as collaborating in the ring, beyond the agreement to abide by the rules; however, this style is often exhibited unknowingly. For example, few fights will continue long without one fighter assuming the role of aggressor. Fans get unruly with sparse interaction, ultimately leading to one fighter assuming an alternate style. In fights where mutual respect has been substantiated, combatants may actually work together to conserve energy. The counterpunch is a reactive strategy that depends on actions of the other. Each fighter creates windows of opportunity for themselves and the other. As for the referee, he is an impartial judge; yet he is ready to assist either combatant when unfair advantage has been levied through either an infraction of the rules or physical incapacitation. While physical domination is a fighter’s goal, illegal blows include those when a fighter is unable to defend himself. Boxers and their corner representation make appeals throughout a match. The degree to which this information is processed into decision making is up to the referee. While this may on the surface resemble arbitration rather than negotiation, the professional boxing referee operating with this style is open to input from participants and is actively engaged with the fighters. The referee in this style could also be interpreted as negotiating with himself for the benefit of the fighters and the sport. The good referee works with both fighters, while not showing favoritism beyond the enforcement of fight protocol.

Compromising – Judge Like Solomon

This style is perhaps the one most in need of alternate imagery from the original language of Thomas and Kilmann. Compromising means making concessions to the other in order to gain ground on those terms most important to you. Sportsmen do not typically envision compromise as a useful style. However, if we examine the motivating forces (the axes in the style chart), we find a related style, also a balance between cooperation and assertiveness. This style can easily move into any of the other styles with small shifts in motivation. We choose to rename this style Judge Like Solomon to capture the keen sense of fairness exhibited by Solomon, as recorded in Hebrew scripture: in particular, the incident of the two women approaching Solomon with but one child, both claiming to be the mother. Exercising great wisdom, he called for the child to be cut in half (ostensibly a compromise), giving an equal portion to each woman. The woman yielding her claim, in order to save the child, was awarded the baby, as having shown herself to be the true mother. What appeared at first to be an extremely bad compromise was thus revealed instead to be judiciousness of a higher order. We believe there is wisdom in the fact that the two could be confused.

While combatants may not claim to operate in the arena of compromise, the appropriate strategy strikes a balance between offense and defense, aggression and caution. The skilled fighter can operate with such a balance, reserving opportunity to both seize advantage and protect against disadvantage. Sometimes the best “cooperative” strategy is simply to wait, to prolong the window of opportunity. Meanwhile, the professional boxing referee seeks to use this conflict management strategy for preference, working with the combatants, but ever ready to interject himself between fighters as the authority figure in the ring. We envision this style, therefore, not as one of com- promise in its classic sense, but rather as one of judicious and decisive balance.

Avoiding – Avoid Like a Politician

We can easily identify the avoidance tactic with politicians who place reputation and votes over positions and policies. The avoiding strategy is often portrayed in boxing as both an offensive and defensive tool. Against a slower opponent, a boxer may choose to maintain advantage through constant motion. Avoiding can also be used to great advantage if there is a marked difference in reach. While the jab seldom results in a knockout, it scores points, nevertheless. Avoidance could likewise be a tactic to counter an obvious advantage in power. A boxer knowing, he cannot effectively trade blows toe-to-toe can exercise avoidance. From a conflict management style, Avoid Like a Politician is low on both the cooperation and assertiveness scales. That does not make it an ineffective strategy in boxing, as exhibited by the younger Ali in his extensive use of motion, captured in his mantra “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”; however, it is not a desirable dominant conflict management strategy for a boxing referee. Such a referee fails to control a fight, endangering the lives of the combatants. Under some circumstances, a referee can avoid micromanagement of a fight without giving undue advantage; but a referee exercising avoidance too much will be seen as disengaged or ill-equipped for the position, especially at the professional level.

Accommodating – Delegate Like a Diplomat

The accommodating style is quick to please, surrendering leadership or control; but while this type of behavior is exhibited in sports, it is seldom seen in boxing referees. Thus, we have labeled this conflict management style as Delegate Like a Diplomat. A diplomat goes to great lengths not to offend and always errs on the side of relationship. This style is seldom effectively used by boxers, though there is historical precedent in Ali’s rope-a-dope strategy deployed against a younger, stronger, but less durable Foreman. The tactic coined as rope-a-dope by Ali refers to an invitation to the opponent to take un-countered punches while he assumes a low-energy, highly protective stance using the ringside ropes as shock absorbers. Using his arms and gloves as protective equipment to avoid debilitating damage, he planned to tire the opponent with extended invitations to take their best shot. Once his opponent’s energy was spent, Ali became the aggressor.

In general, to surrender (temporarily) to the opponent is almost always a defensive strategy by a hurt fighter trying to protect himself just long enough to regain his faculties. A referee using the delegating strategy of conflict management may purposefully bend the rules to protect a fighter or counter an advantage.

A referee using this strategy can easily be viewed as one showing favoritism in the ring. Another form of delegation concern scoring, knowing there are other judges scoring the fight. The referee could get so involved with other aspects of officiating as to lose track of his responsibility to score the fight properly. In this case, he is not delegating to the combatants, but rather to the other professional judges, who, however, lack the referee’s ability to manipulate his frame of reference for optimal viewing angle. The professional boxing referee ought to have the most reliable assessment of scoring blows. Another example of delegating by the referee would be indirectly addressing conflict to preserve relationship or, as in the case of Holyfield-Tyson, seeking higher authority, as in a boxing commissioner or doctor.

Table 1 categorizes how each of these five conflict management styles would offer a different response to the delivery of a low blow by one fighter against another.

Figure 1. Proposed Thomas-Kilmann conflict management styles reinterpreted for application in combative adjudicated sports by Chamoun et.al.

Table 1. Illustrative potential actions in response to an illegal punch.

| CONFLICT MANAGEMENT STYLE | ACTION |

| Fight like a Spartan | Stop the action and penalize the guilty fighter |

| Do Business like Phonetician | Stop the action and verbally warn both fighters |

| Judge Like Solomon | Stop the action, issue a warning, and access the ability for violated party to continue |

| Avoid Like a Politician | Let the fight continue as long as both fighters are physically able |

| Delegate like a Diplomat | Stop the action and warn each corner |

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT STYLE

In the Fight Like a Spartan style, the referee would immediately exercise a penalty based upon his observation and interpretation of the facts. In the Facilitate Like a Phoenician style, the referee would acknowledge the observation and recite the rules to both parties equally, to preserve relationships. In the Judge Like Solomon mode, the referee would stop the action and exhibit concern for both the rules and the fighters, especially the one who was placed at a disadvantage. In the Avoid Like a Politician style, the referee would apply the adage, no harm, no foul. As Delegate Like a Diplomat, the referee might fail to address the combatants directly, preserving relationships and choosing rather to allow the coaches in each corner to police the actions of their principals. These are all actions that can and do take place in boxing in response to the identical in-ring infraction.

Conclusion

The reinterpretation of conflict management styles for combative sports, and professional boxing in particular, leads to specialized imagery that better fits the substance of what we argue is largely a disguised negotiation. In particular, the compromising style is replaced with a more meaningful interpretation, for competitive sports, of the balance between cooperation and assertiveness. Classification of styles aids in self-awareness, along with better management of interactions with others displaying tendencies identifiable using this schema. Conflict management styles can be dynamic, but dominant styles can emerge as primary. Sports examples help solidify terms and concepts for audiences who are not familiar or comfortable with negotiation theory or traditional classroom learning experiences. Roles that are typically projected to display only one or two styles, due to the win-lose nature of the game, turn out on examination actually to cover a wide gamut of possible styles. Perhaps the terminology as applied here to the professional boxing referee could be extended to other participants and other sports, revealing still more venues in which negotiation is pervasive if generally unrecognized.

In addition, this new model may be more appropriate when dealing with different generations at the business environment such as millennials, centennials, Gen X and Baby Boomers.

blog information’s sources:

Chamoun-Nicolas, H., R. D. Hazlett, R. Mora, G. Mendoza, and M. L. Welsh. 2014. Negotiation and Professional Boxing. In Educating Negotiators for a Connected World: Volume 4 in the Rethinking Negotiation Teaching Series, edited by C. Honeyman, J. Coben, and A. Wei-Min Lee. St. Paul, MN: DRI Press.Chamoun-Nicolas, H., R.D. Hazlet, J. Estwanik, Mora R. and Mendoza, G. 2017 Negotiation and Professional Boxing: The Ringside Physician. The Negotiators Desk Reference, NDR editors C. Honeyman and A.K. Schneider. St Paul, MN:DRI Press.

Chamoun-Nicolas, H., and R.D. Hazlett Negotiate like a Phoenician 2008 KN

Chamoun-Nicolas, H., E. Martin, H. Pereda, and R.D. Hazlett Transcend Quo Vadis Negotiator 2016 KN