What is the Primary Activity of a Catholic University? Intellectual Charity (Properly Understood)

Amid all of the good things that take place at a flourishing Catholic university, what is the essential activity that sets it apart from other Catholic institutions – such as Catholic hospitals, charities and parishes – and other universities that are not Catholic? In this year’s inaugural “Formation for Mission” seminar for new faculty and staff, we had the occasion to consider “intellectual charity” as the primary dimension of the Catholic university.

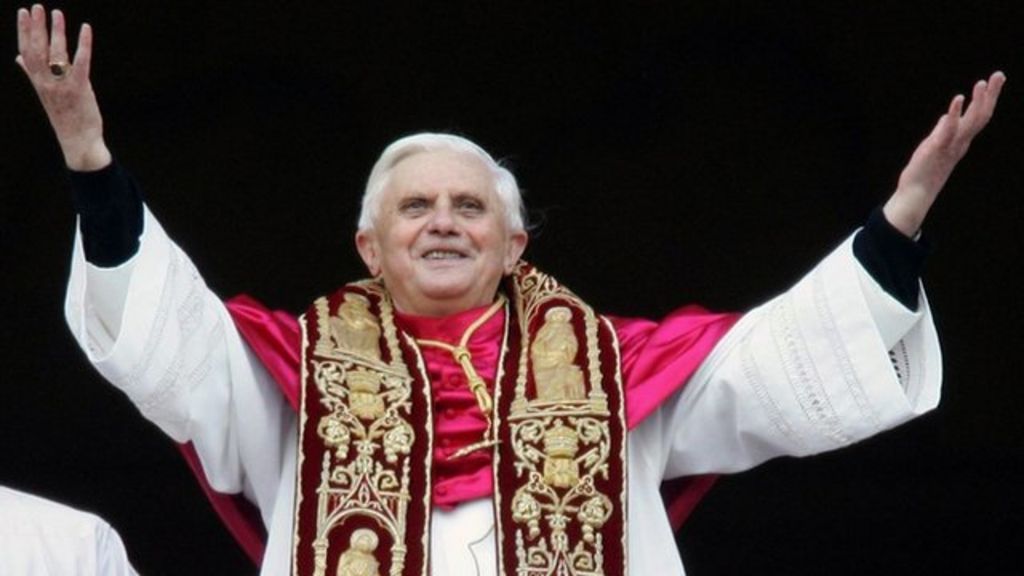

The challenges of understanding this animating principle emerged as the group discussed an essay by Christopher O. Blum, which itself is born from an address of Benedict XVI. Too often, this form of charity is confused with giving an author “the benefit of the doubt,” cultivating a humanistic fellow-feeling for other members of the academic community, or a relativism that rejects any strong truth claims in the name of “intellectual humility.”

And very quickly, by merely mentioning the word “truth,” we may find that we have summoned relativism in its expressive individualistic form—“Your truth is your truth, and my truth is my truth”—or in the seemingly more sophisticated form expressed by Pontius Pilate, “What is truth?”

But in his address, Benedict accepts the common sense idea that there is truth—i.e., we can attain to an accurate (albeit always incomplete) correspondence between reality and our own understanding—and makes clear that intellectual charity is simply that love by which we lead students to truth. Thus, affirming that we can know truth objectively and then leading students to that truth—and ultimately the Truth who stands behind all secondary truths—is the way in which professors, administrators, and staff of a Catholic academic community primarily love their students.

This understanding of intellectual charity does not reject the implied goods suggested above in their deeper forms: the idea that we should respectfully read authors as they hope to be read, honor the dignity of all members of our community as creatures made in the image and likeness of God, or be willing to consider with grace those views that might be opposed our own. Indeed, each of these should be present within a Catholic academic community and should complement and support the essential work of intellectual charity: leading students into truth as an act of love.

To further clarify intellectual charity, we should distinguish this charity specific to a university, by definition devoted primarily to the the formation of the intellect (within a larger mission of formation), and the forms of charity specific to institutions that serve in other ways. Though this is carried out above all by professors directly within and around the classroom, administrators and staff do this through their own participation in and support of the life of learning on campus. Through these direct and indirect efforts, intellectual charity is realized within an academic community.

This does not mean that intellectual charity is the only charity that constitutes the life of the Catholic university. But it is the primary one. Other forms of charity are brought into being and lived out—through the sacramental life, campus ministry, service projects, a pro-life witness, and the critical work of student affairs—but intellectual charity is the fundamental and animating form.

As an aside, we should note that Newman himself understood that attention to a well-ordered residential life and the spiritual life of the students is essential to the “integrity” of the Catholic university even if they are not essential to its “Idea.” In a similar way, breathing is necessary for the integrity of human life, even if it is not part of the classical definitions of what it means to be human.

And yet, leading students to truth as an act of love is the very heartbeat of the Catholic university—the very reason for its existence—to unbind students from the realm of shadows and lead them into the light of wisdom. This work of intellectual charity is not the primary work of Catholic charities, Catholic hospitals, and other apostolates. Ultimately, all of these should lead those whom they serve toward the one who is Wisdom itself, but Catholic universities do this in a particular and unique way. At the very center of this way is the great Catholic intellectual tradition that reaches out to encompass every discipline and sphere of knowledge within a coherent whole.

This emphasis and focus should not be understood to exclude spheres of the university beyond the classroom and professoriate. Indeed, intellectual charity should permeate and animate every dimension of the Catholic university. It should take place across the university and outside the classroom. It can flow through every influential conversation with a member of the staff or administration that illuminates some aspect of reality that a student may have only understood incompletely. It can happen at a lunch with a member of Student Affairs, in a small group run by campus ministry, or in the confessional. And even those working behind the scenes play a critical role by creating the conditions necessary for teaching and learning in the classroom and education in more informal settings to take place.

It can happen with students, with colleagues, with those external to the university. Leading others to truth in love—within and beyond the classroom—knows no bounds.

In sum, every act of leading a student (or colleague, or someone in contact with the university) deeper into wisdom is an act of “intellectual charity.” This act aims at “fostering the true perfection and happiness of those to be educated,” culminating in an encounter with Christ who is Truth itself.

But there is more

In his essay, Blum suggests that there are three essential characteristics of intellectual charity. First, that it is “a warm and personal compassion responding to the fact that truth is a good of persons, that is, that truth is not found principally in books but rather is at home deep in the interior of the human mind and heart.” Second, that it depends on the recognition that those of us who teach in any capacity participate in a beautiful exchange of gifts. As recipients of a gift—the truth that others have led us to—we also receive a responsibility—to lead others in turn to truth. Third, intellectual charity depends on the cultivation of the interior life of prayer and contemplation, which in turn depends on leisure. If intellectual charity is reduced to activism, we will soon deplete our ability to love and to know. We must, like Mary Magdalen, choose the better part.

Furthermore, as one of our interlocutors in the seminar emphasized, intellectual charity is a virtue. As such it is a stable disposition that is not easily achieved and not easily lost. But when it is built up through repeated and intentional action, it brings the one who possesses it to a steady readiness to act: at any moment a student or colleague might stand in need of being led toward truth and we—as members of the academic community—should be prepared to love generously in that way at that time.

In this journey there are other peaks that will rise before us. Benedict XVI suggested several. First, as indicated above, the ultimate destination of our leading must be kept in mind: our highest goal is communion with Christ. Even if our discipline is the history of music, and this is the truth into which we proximately are leading our students, we keep always in mind the larger vision in which music is part of culture, culture is “what we do with nature,” and God himself is the author of nature. In short, every act of teaching and learning can be illuminated by the truth of our ultimate purpose: the beatific vision and communion in the life of the Trinity.

This suggests another peak to which Benedict refers: the practice of “‘intellectual charity’ upholds the essential unity of knowledge against the fragmentation which ensues when reason is detached from the pursuit of truth.” This recalls Newman’s circle of the disciplines through which the true university not only includes but also orders and integrates all of the disciplines, including those disciplines only emerging as spheres of knowledge today.

And Benedict XVI also points us toward a fundamentally human concern: there can be no real freedom that does not accord with truth. Intellectual charity guides “the young towards the deep satisfaction of exercising freedom in relation to truth.” This discovery that truth can be achieved and is not merely a social construct becomes a guide for flourishing that is immediately liberating. Indeed, this is one of the single most important truths to which we can lead our students: “freedom” cut off from the truth of the human person and larger reality is not true freedom. The vista of a life-long adventure of discovery and service—including self-discovery, the discovery of culture, nature, and God—will open up before our students as we lead them toward truth. “Here they will experience ‘in what’ and ‘in whom’ it is possible to hope and be inspired to contribute to society in a way that engenders hope in others.”

How different this is from the implicit “charity” that marks so much of higher education: a reductive and sentimental expressive individualism that is disconnected from truth and ordered to no objective and trustworthy fulfillment. A Catholic university need not offer its students stones for bread.

We are in debt to Benedict XVI for clarifying this virtue and to Christopher Blum for reminding us of its relevance today.