Andy Warhol Captures Bold History at UST

Andy Warhol Portrait of Dominique; 1969 Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen; 40 × 40 in. (101.6 × 101.6 cm)

The Menil Collection, Houston

Fifty years ago, Andy Warhol first stepped onto the University of St. Thomas campus with a mission. Laboring with faculty, he was to collaborate with other contemporary artists on a religious art exhibition for the Catholic chapel at the 1968 World’s Fair in San Antonio. This partnership began in 1964 when Dominique de Menil, the chair of the Art History Department, commissioned Warhol to make a film that reflected his religious sentiments. That was a daring move, given the fact that his art had only been known for its irreverence toward tradition and quirky (but sometimes brutal) banality. Dominique heard rumors there was more to Warhol than his critics were printing.

Andy Warhol was born into a first-generation immigrant family from what is now Slovakia. They were devout Byzantine-rite Catholics: Their worship resembled Russian Orthodoxy, while being in full communion with the Roman Church. Growing up in a poor Pittsburgh ghetto, Warhol was a frail and sick child, often shut-in at home and cared for by his mother. Their house was decorated with low quality, mass-produced religious imagery alongside throw-away popular media, such as comic books and magazines. In contrast, when he went to church, he was surrounded by timeless handmade icons. These two distinct realms helped him bifurcate his personality into two separate identities: a public mask of someone as superficial as the society around him, covering a deeply private person with rigorous religious practice.

In 1949, he moved to New York City, where he soon found work as a graphic designer, illustrating advertisements and magazines, and creating installations in department store windows. A few years later, his mother moved in with him, and every morning they would pray together from an Old Slavonic devotional; she lived with him for the next 20 years. His two-faced persona allowed him to climb the corporate ladder from a poor underdog to the top dog on Madison Avenue; in other words, his outer image as a rebel served as armor that protected his frail inner self from harsh criticism of a highly-competitive industry. His whimsical artistic style captured the spirit of the 1950s consumer culture, and eventually, he succeeded in becoming the most sought after commercial artist of the city; however, by 1960 he wanted more. Only monumental artists achieved permanency by having their creations hang on museum walls, and that is what he sought. Gradually he succeeded in elevating the market-driven imagery of graphic design—things like Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles—into items that museums now collect as “fine art,” thus pioneering the concept of “popular art” (aka pop art). In a sense, Warhol’s success was rooted in his merging of the two worlds of his childhood—the mechanically-made images of daily life with the larger-than-life fine art he experienced at church. That approach was innovative and influential, perfectly synchronized with the secularization of American society. In a world shaped by capitalism and popularity, soon Warhol would be dubbed “the Pope of Pop.”

At the time Warhol was invited to Houston, Dominique de Menil had reasons to be apprehensive. He had recently scandalized the 1964 New York World Fair by providing a large (20 feet by 20 feet) silkscreen called “13 Most Wanted Men,” which greeted patrons at the entrance. At first glance, viewers assumed the image showcased New York’s best and brightest, but with a closer look they realized that it was 13 mugshots from that state’s criminal records. Ouch. Not really what the organizing committee had expected. Like many of his early works, it was meant to be ironic and, perhaps, a mirror of society—a reflection of a darker reality that few wanted to view. If he was so brazen toward his home crowd, what was Andy planning for Texas?

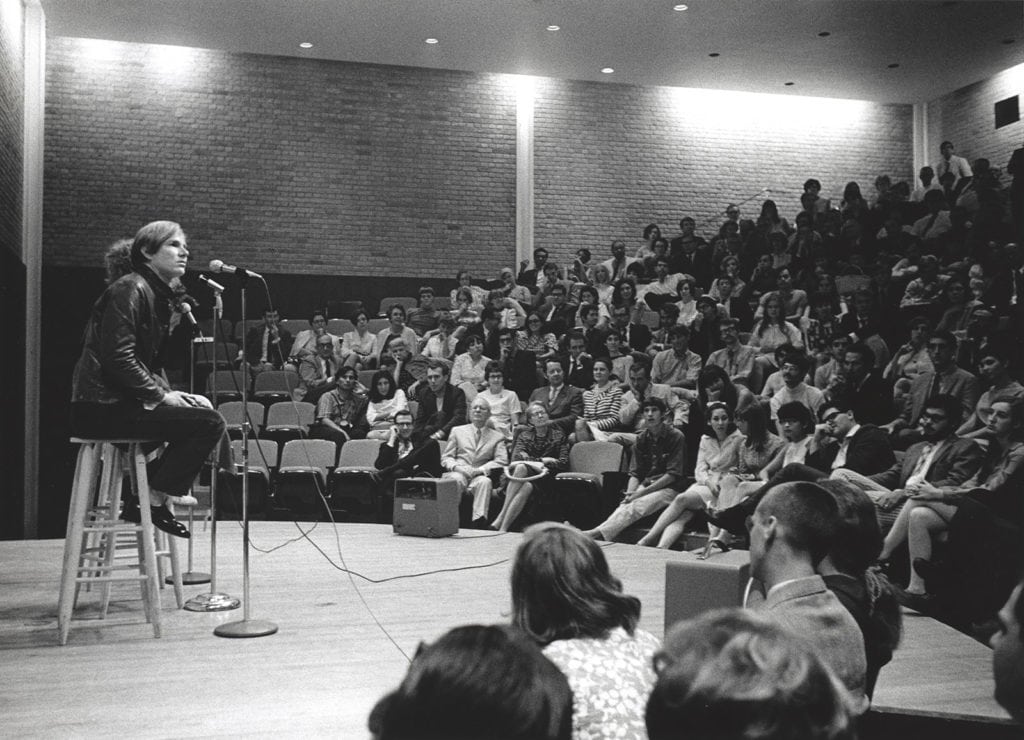

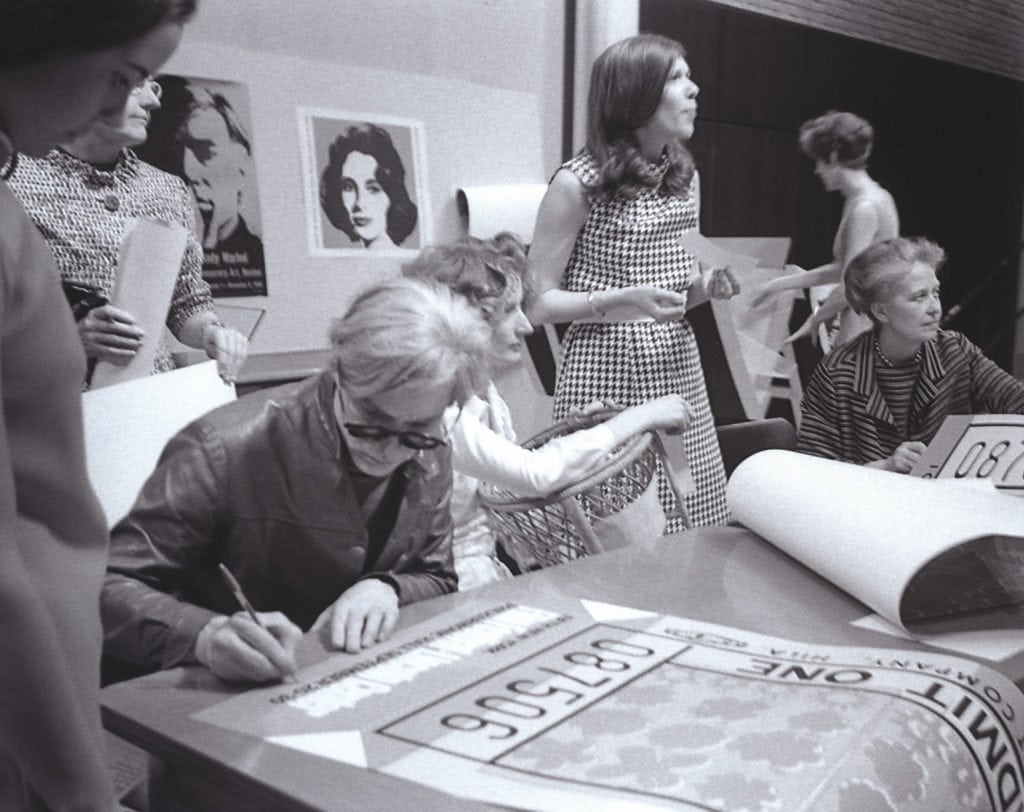

Uncharacteristically, Warhol took Mrs. de Menil and the University of St. Thomas seriously. Glimpses of his religious alter-ego emerged while he was on campus. Perhaps this was a result of him leaving behind his avaricious and celebrity-chasing New York community and replacing it, briefly, with a sincere and down-to-earth crowd of faculty and students. I’ve been told that the Basilian priests on campus withheld their judgments and welcomed him with genuine curiosity. Warhol must have stood out in Texas—much like his art—outlandish, awkward and anti-heroic. His creepy blond wig, sunglasses and leather jacket appeared out-of-place on campus where most men wore conservative ties and the priests, collars. Nevertheless, Warhol gave lectures, critiqued student’s art and visited local art exhibitions. At one event he met a UST art history student, Fred Hughes, and was impressed by his intelligence and charisma. For the next 25 years, Hughes would manage Warhol’s studio and business, while publishing the avant-garde magazine Interview. Many credit Hughes for successfully “rebranding” Warhol for the 1970s and 1980s; when the artist died, Hughes became the executor of his will.

- Andy Warhol at St. Thomas in 1968 Jones Hall

- Photographer: Hickey-Robertson. Courtesy of the Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston.

- Photographer: Anthony Flores. The Menil Collection, Houston.

- American Pop artist Andy Warhol meets Pope John Paul II in Vatican CIty. Photographer: Lionello Fabbri

For the 1968 World’s Fair, Warhol envisioned the Catholic chapel decorated with a film projection of a setting sun. To him, the most spiritual art was found in creation itself. Over the course of four years he filmed several such scenes but never achieved the desired results, and the chapel project never materialized. Raw footage of his Sunset film survives, and in 2016 the Menil Collection exhibited it for the first time to the public. It was interesting to see the audience reaction to the evocative deep purples and vanilla skies captured on celluloid—and yes, there is something substantial, if not spiritual, in Warhol’s cinematography, in contrast to his more famous superficial prints. His films showcase a superb technical and visual sensibility, but this was undermined by his inability to choose quality scripts and qualified actors.

Warhol’s last appearance at UST was in May of 1968. At that time, he premiered two films, **** (Four Stars) and Imitation of Christ, for the Houston community. The latter’s title was based on the devotional by Thomas à Kempis written around 1420 and seemed fitting for the modern-medieval aesthetic that was being developed within the UST’s Art Museum in Jones Hall (which would later form the nucleus of the Menil Collection). He received a lukewarm reception by students and the press, since both films, seemingly, did not live up to the expectations set by their lofty titles. Afterward, he gave a lecture in Jones Hall to a reticent crowd unsure about the artistic merits of these productions. Some thought they were participants in a practical joke. If so, Warhol was not laughing; he was as deadpan as ever. Incidentally, a month later in his New York studios, he was gunned down by an aspiring actress. While his life drained away, he prayed that if he survived, he would attend Mass every Sunday, and according to his friends, he kept that promise for the next 19 years.

Warhol’s private devotion began to express itself in more public ways. Sometimes he volunteered to serve food to the homeless at New York’s soup kitchens; he was also generous in redistributing his massive wealth to charities around the city. His most conspicuous act of piety was his pilgrimage to Rome, where he arranged a private audience with Pope John Paul II. Perhaps this was inevitable—“the Pope of Pop” had to meet the actual Pope—and they shared many things in common: A Catholic faith rooted in Slavic cultures and both experimented with the dramatic arts. After this encounter, Warhol shifted toward religious iconography, especially the image of the cross.

The powerful art critic Robert Hughes — himself a product of a Catholic university — was always a harsh critic of Warhol. He once wrote “no mass public has ever felt at ease with Warhol’s work.” That is the case with me as an artist and professor of Catholic art; Warhol’s “religious” images are so ambiguous that they can be interpreted equally as either a form of worship or sacrilege—depending on the viewer’s attitude. As I write this, I recognize that this quality may be one reason why Warhol has had a lasting influence, especially on current fashion, technology and social media. He was a pioneer of relativism who never imposed his views, so his worldview is still being debated among scholars. He asked nothing of his audience. He never claimed to be original or important. As a genuine American product, he simply allowed the market to judge his value, and it has clearly spoken—one of his early prints sold in 2013 for $105 million. Today Warhol’s reprints are, themselves, reprinted everywhere, from T-shirts to shoes, handbags to coffee mugs, and he is ever-referenced in songs, films and textbooks. This year, the biggest art event has been the “David Bowie is” exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, which demonstrates the profound influence that Warhol’s style, if not his aesthetics, had on many other artists of the late 20th century.

Warhol is just one thread woven into the multi-color fabric of UST’s legacy. Certainly, he was a polarizing figure in the 1960s and still is today; however, if we view him within the long arc of art history, we can see the “big picture.” Someone like Warhol was bound to emerge after the graphic designs of Toulouse-Lautrec and Matisse were accepted as works of “fine art,” coinciding with the market’s desire for ambivalent messaging that Duchamp and Dali offered—and all these artists had a Catholic upbringing, maintaining some relationship with the Church throughout their lives. To secular scholars, these artists’ Catholicism is perplexing, and this aspect, thus, is often ignored. To traditionalists, these artists had moral indiscretions and/or recalcitrant personalities, not to mention nonconformist attitudes, and so they are avoided. It is possible to find a middle ground—or as Aquinas called it, via tertia—and UST’s fine arts programs, including music and drama, have always tried to maintain a balanced approach toward complex artistic issues. Catholicism is so rich because of its complexity and expressive diversity. As one body has many parts, and each is necessary for a proper functioning organism, the Church has always supported the Fine Arts as a vital conduit to spread its doctrines. The problem with Warhol is that he was hardly doctrinaire.

Warhol’s time at UST may have stamped a lasting impression on him. Before his death in 1987, he became obsessed with the Body of Christ in his final project called the “Last Supper” (variations on Da Vinci’s work of the same name). This series remains the largest religious-content artwork created by any American artist. The truth is one cannot understand Warhol’s influence worldwide without coming to terms with his religious faith, which shaped his attitudes toward humanity. He embraced all levels of society (rich-poor, saintly-decadent, celebrities-rejects, etc.). This openness gave him insights regarding all human creativity manifested in fads, fashion and merchandising. Currently the Vatican Museum is organizing an art exhibition in 2019 that will further examine Warhol’s religious oeuvre. It will take place within the Braccio di Carlo Magno, which was designed by the famous Catholic artist Bernini in 1667. The juxtaposition between pop style within a Baroque space will be jarring, but not indecorous, since both styles are known for their theatricality and flamboyancy. I wonder if this Vatican exhibit would have taken place if, 50 years ago, University of St. Thomas did not take a chance and invite a controversial artist to explore his spiritual side.